- Home

- Blood Harvest

S. J. Bolton

S. J. Bolton Read online

Blood Harvest

S. J. Bolton

Contents

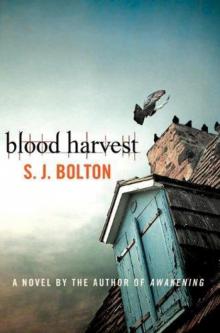

Cover

Title

Copyright

Dedication

Map

About the Author

Also by S. J. Bolton

Prologue

Part One: Waning Moon

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Part Two: Blood Harvest

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Part Three: Day of the Dead

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Part Four: Longest Night

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Chapter 74

Chapter 75

Chapter 76

Chapter 77

Chapter 78

Chapter 79

Chapter 80

Chapter 81

Chapter 82

Chapter 83

Chapter 84

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 1.0

Epub ISBN 9781407054568

www.randomhouse.co.uk

TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

61–63 Uxbridge Road, London W5 5SA

A Random House Group Company

www.rbooks.co.uk

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Bantam Press an imprint of Transworld Publishers

Copyright © S.J. Bolton 2010

S.J. Bolton has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

This book is a work of fiction and, except in the case of historical fact, any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBNs 9780593064115 (hb) 9780593064122 (tpb)

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Addresses for Random House Group Ltd companies outside the UK can be found at: www.randomhouse.co.uk The Random House Group Ltd Reg. No. 954009

The Random House Group Limited supports The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), the leading international forest-certification organization. All our titles that are printed on Greenpeace-approved FSC-certified paper carry the FSC logo. Our paper procurement policy can be found at www.rbooks.co.uk/environment

Typeset in 11.5/14pt ACaslon by Falcon Oast Graphic Art Ltd. Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Mackays, Chatham, ME5 8TD.

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

For the Coopers, who built their big, shiny new house

on the crest of a moor …

‘Battle not with monsters, lest ye become a monster, and if you gaze into the abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.’

Friedrich Nietzsche, German philosopher (1844–1900)

‘She’s been watching us for a while now.’

‘Go on, Tom.’

‘Sometimes it’s like she’s always there, behind a pile of stones, in the shadow at the bottom of the tower, under one of the old graves. She’s good at hiding.’

‘She must be.’

‘Sometimes she gets very close, before you have any idea. You’ll be thinking about something else when one of her voices jumps out at you and, for a second, she catches you out. She really makes you think it’s your brother, or your mum, hiding round the corner.’

‘Then you realize it’s not?’

‘No, it’s not. It’s her. The girl with the voices. But the minute you turn your head, she’s gone. If you’re really quick you might catch a glimpse of her. Usually, though, there’s nothing there, everything’s just as it was, except...’

‘Except what?’

‘Except now, it’s like the world’s keeping a secret. And there’s that feeling in the pit of your stomach, the one that says, she’s here again. She’s watching.’

S. J. Bolton was born in Lancashire. She is the author of two previous critically acclaimed novels, Sacrifice and Awakening, out now in paperback. Sacrifice was nominated for the International Thriller Writers Award for Best First novel and, in France, for the prestigious Prix Polar SNCF Award. The Blood Harvest is her third novel. She lives near Oxford with her husband and young son.

For more information about the author and her books, visit her website at www.sjbolton.com

Also by S. J. Bolton

Sacrifice

Awakening

For more information on S. J. Bolton and her books, see her website at

www.sjbolton.com

Prologue

3 November

IT HAD HAPPENED, THEN; WHAT ONLY HINDSIGHT COULD HAVE told him he’d been dreading. It was almost a relief, in a way, knowing the worst was over, that he didn’t have to pretend any more. Maybe now he could stop acting like this was an ordinary town, that these were normal people. Harry took a deep breath, and learned that death smells of drains, of damp soil and of heavy-duty plastic.

The skull, less than six feet away, looked tiny. As though if he held it in his palm, his fingers might almost close around it. Almost worse than the skull was the hand. It lay half hidden in the mud, its bones barely held together by connective tissue, as though trying to crawl out of the ground. The strong artificial light flickered like a strobe and, for a second, th

e hand seemed to be moving.

On the plastic sheet above Harry’s head the rain sounded like gunfire. The wind so high on the moors was close to gale force and the makeshift walls of the police tent couldn’t hope to hold it back completely. When he’d parked his car, not three minutes earlier, it had been 3.17 a.m. Night didn’t get any darker than this. Harry realized he’d closed his eyes.

Detective Chief Superintendent Rushton’s hand was still on his arm, although the two of them had reached the edge of the inner cordon. They wouldn’t be allowed any further. Six other people were in the tent with them, all wearing the same white, hooded overalls and Wellington boots that Harry and Rushton had just put on.

Harry could feel himself shaking. His eyes still closed, he could hear the steady, insistent drumbeat of rain on the roof of the tent. He could still see that hand. Feeling himself sway, he opened his eyes and almost overbalanced.

‘Back a bit, Harry,’ said Rushton. ‘Stay on the mat, please.’ Harry did what he was told. His body seemed to have grown too big for itself; the borrowed boots were impossibly tight, his clothes were clinging, the bones in his head felt too thin. The sound of the wind and the rain went on, like the soundtrack of a cheap movie. Too much light, too much noise, for the middle of the night.

The skull had rolled away from its torso. Harry could see a ribcage, so small, still wearing clothes, tiny buttons gleaming under the lights. ‘Where are the others?’ he asked.

DCS Rushton inclined his head and then guided him across the aluminium chequer plating that had been laid like stepping-stones over the mud. They were following the line of the church wall. ‘Mind where you go, lad,’ Rushton said. ‘Whole area’s a bloody mess. There, can you see?’

They stopped at the far edge of the inner cordon. The second corpse was still intact, but looked no bigger than the first. It lay face-down in the mud. One tiny wellington boot covered its left foot.

‘The third one’s by the wall,’ said Rushton. ‘Hard to see, half- hidden by the stones.’

‘Another child?’ asked Harry. Loose PVC flaps on the tent were banging in the wind and he had to half-shout to make himself heard.

‘Looks like it,’ agreed Rushton. His glasses were speckled with rain. He hadn’t wiped them since entering the tent. Maybe he was grateful not to see too clearly. ‘You can see where the wall came down?’ he went on.

Harry nodded. A length of about ten feet of the stone wall that formed the boundary between the Fletcher property and the churchyard had collapsed and the earth it had been holding back had tumbled like a small landslide into the garden. An old yew tree had fallen with the wall. In the harsh artificial light it reminded him of a woman’s trailing hair.

‘When it collapsed, the graves on the churchyard side were disturbed,’ Rushton was saying. ‘One in particular, a child’s grave. A lass called Lucy Pickup. Our problem is, the plans we have suggest the child was alone in the grave. It was freshly dug for her ten years ago.’

‘I’m aware of it,’ said Harry. ‘But then …’ He turned back to the scene in front of him.

‘Well, now you see our problem,’ said Rushton. ‘If little Lucy was buried alone, who are the other two?’

‘Can I have a moment with them?’ Harry asked.

Rushton’s eyes narrowed. He looked from the tiny figures to Harry and back again.

‘This is sacred ground,’ said Harry, almost to himself.

Rushton stepped away from him. ‘Ladies and gentlemen,’ he called. ‘A minute’s silence, please, for the vicar.’ The officers around the site looked up. One opened his mouth to argue but stopped at the look on Brian Rushton’s face. Muttering thanks, Harry stepped forward, closer to the cordoned area, until a hand on his arm told him he had to stop. The skull of the corpse closest to him had been very badly damaged. Almost a third of it seemed to be missing. He remembered hearing about how Lucy Pickup had died. He took a deep breath, aware that everyone around him was motionless. Several were watching him, others had bowed their heads. He raised his right hand and began to make the sign of the cross. Up, down, to his left. He stopped. Closer to the scene, more directly under the lights, he had a better view of the third corpse. The tiny form was wearing something with an embroidered pattern around the neck: a tiny hedgehog, a rabbit, a duck in a bonnet. Characters from the Beatrix Potter stories.

He started to speak, hardly knowing what he was saying. A short prayer for the souls of the dead, it could have been anything. He must have finished, the crime-scene people were resuming their work. Rushton patted his arm and led him out of the tent. Harry went without arguing, knowing he was in shock.

Three tiny corpses, tumbled from a grave that should only have contained one. Two unknown children had shared Lucy Pickup’s final resting place. Except one of them wasn’t unknown, not to him anyway. The child in the Beatrix Potter pyjamas. He knew who she was.

Part One

Waning Moon

1

4 September (nine weeks earlier)

THE FLETCHER FAMILY BUILT THEIR BIG, SHINY NEW HOUSE on the crest of the moor, in a town that time seemed to have left to mind its own business. They built on a modest-sized plot that the diocese, desperate for cash, needed to get rid of. They built so close to the two churches – one old, the other very old – that they could almost lean out from the bedroom windows and touch the shell of the ancient tower. And on three sides of their garden they had the quietest neighbours they could hope for, which was ten-year-old Tom Fletcher’s favourite joke in those days; because the Fletchers built their new house in the midst of a graveyard. They should have known better, really.

But Tom and his younger brother Joe were so excited in the beginning. Inside their new home they had huge great bedrooms, still smelling of fresh paint. Outside they had the bramble-snared, crumble-stone church grounds, where story-book adventures seemed to be just waiting for them. Inside they had a living room that gleamed with endless shades of yellow, depending on where the sun was in the sky. Outside they had ancient archways that soared to the heavens, dens within ivy that was old and stiff enough to stand up by itself, and grass so long six-year-old Joe seemed drowned by it. Indoors, the house began to absorb the characters of the boys’ parents, as fresh colours, wall-paintings and carved animals appeared in every room. Outdoors, Tom and Joe made the churchyard their own.

On the last day of the summer holidays, Tom was lying on the grave of Jackson Reynolds (1875-1945), soaking up the warmth of the old stone. The sky was the colour of his mother’s favourite cornflower-blue paint and the sun had been out doing its stuff since early morning. It was a shiny day, as Joe liked to say.

Tom wouldn’t have been able to say what changed. How he went from perfectly fine, warm and happy, thinking about how old you had to be to try out for Blackburn Rovers to … well … to not fine. But suddenly, in a second, football didn’t seem quite so important. There was nothing wrong, exactly, he just wanted to sit up. See what was nearby. If anyone …

Stupid. But he was sitting up all the same, looking round, wondering how Joe had managed to disappear again. Further down the hill, the graveyard stretched the length of a football field, getting steeper as it dropped lower. Below it were a few rows of terraced houses and then more fields. Beyond them, at the bottom of the valley, was the neighbouring town of Goodshaw Bridge where he and Joe were due to resume school on Monday morning. Across the valley and behind, on just about every side, were the moors. Lots and lots of moors.

Tom’s dad was fond of saying how much he loved the moors, the wildness, grandeur and sheer unpredictability of the north of England. Tom agreed with his dad, of course he did, he was only ten, but privately he sometimes wondered if countryside that was predictable (he’d looked the word up, he knew what it meant) wouldn’t be a bad thing. It seemed to Tom sometimes, though he never liked to say it, that the moors around his new home were a little bit too unpredictable.

He was an idiot, of course, it went without saying.

&n

bsp; But somehow, Tom always seemed to be spotting a new lump of rock, a tiny valley that hadn’t been there before, a bank of heather or copse of trees that appeared overnight. Sometimes, when clouds were moving fast in the sky and their shadows were racing across the ground, it seemed to Tom that the moors were rippling, the way water does when there’s something beneath the surface; or stirring, like a sleeping monster about to wake up. And just occasionally, when the sun went down across the valley and the darkness was coming, Tom couldn’t help thinking that the moors around them had moved closer.

‘Tom!’ yelled Joe from the other side of the graveyard, and for once Tom really wasn’t sorry to hear from him. The stone beneath him had grown cold and there were more clouds overhead.

‘Tom!’ called Joe again, right in Tom’s ear. Jeez, Joe, that was fast. Tom jumped up and turned round. Joe wasn’t there.

Around the edge of the churchyard, trees started to shudder. The wind was getting up again and when the wind on the moor really meant business, it could get everywhere, even the sheltered places. In the bushes closest to Tom something moved.

‘Joe,’ he said, more quietly than he meant to, because he really didn’t like the idea that someone, even Joe, was hiding in those bushes, watching him. He sat, staring at the big, shiny-green leaves, waiting for them to move again. They were laurels, tall, old and thick. The wind was definitely getting up, he could hear it now in the tree-tops. The laurels in front of him were still.

It had probably just been a strange echo that had made him think Joe was close. But Tom had that feeling, the ticklish feeling he’d get when someone spotted him doing something he shouldn’t. And besides, hadn’t he just felt Joe’s breath on the back of his neck?

‘Joe?’ he tried again.

‘Joe?’ came his own voice back at him. Tom took two steps back, coming up sharp against a headstone. Glancing all round, double-checking no one was close, he crouched to the ground.

S. J. Bolton

S. J. Bolton